March 2021

How your proposal is scored

March/2021/

Do you know how your proposal is scored?

In formal procurement processes, evaluators read your offer and then independently score your response to each question. To calibrate the scoring, evaluators may be issued with a scoring guide like the example below:

Why have a scoring guide? To avoid the evaluation degenerating into a relative comparison against other bidders. When we go shopping we might say "I prefer the blue one over the red one" but formal procurement is supposed to compare the responses against the client needs, not against other responses!

Each response is scored out of ten by each evaluator and then the evaluators meet and try to reach consensus (usually not an average) to agree a common score. This score is then multiplied by the weighting for that dimension agreed in the evaluation framework to give an overall result for this criterion.

As an example, if you were appointing an advertising agency innovation might be one important evaluation criterion. It might be weighted 10% of the total non-price evaluation score.

But a glance at the scoring guide above suggests that in this case the scoring guide is almost worse than useless!

What are "our key requirements"?

It is likely that each evaluator will have their own opinion of 'what good looks like' and score accordingly. The scoring guide will not calibrate the scoring unless the evaluation team have discussed and agree what good looks like.

"I know it when I see it" is no substitute for being clear about what you are looking for! Worse than that, the evaluators may score the response against each other. "I liked #2 better than #3" is not good practice, but it happens. While you can't always influence the prospect's scoring processes, you can develop a self-assessment framework before you submit your proposal. Here is an example of a scoring guide focused on innovation:

Imagine that the proposal team could develop a response to the question above using this example as a guide to what "good looks like". Imagine that even if the prospect is dysfunctional and resorts to scoring responses relative to each other, and not against a standard scoring framework, your response had successfully calibrated their understanding of "what good looks like"?

Wouldn't that be worth having?

The ability to self-assess your proposal before you pressed 'send', and also the ability to shape the prospect's understanding of what good looks like!

Wow!

In formal procurement processes, evaluators read your offer and then independently score your response to each question. To calibrate the scoring, evaluators may be issued with a scoring guide like the example below:

Why have a scoring guide? To avoid the evaluation degenerating into a relative comparison against other bidders. When we go shopping we might say "I prefer the blue one over the red one" but formal procurement is supposed to compare the responses against the client needs, not against other responses!

Each response is scored out of ten by each evaluator and then the evaluators meet and try to reach consensus (usually not an average) to agree a common score. This score is then multiplied by the weighting for that dimension agreed in the evaluation framework to give an overall result for this criterion.

As an example, if you were appointing an advertising agency innovation might be one important evaluation criterion. It might be weighted 10% of the total non-price evaluation score.

"Describe how your organisation demonstrates innovation. Using examples sourced from our sector, show how you identify the opportunity to introduce new ways of working either for yourself or for a client, and describe how you supported a client in successfully introducing innovation"

But a glance at the scoring guide above suggests that in this case the scoring guide is almost worse than useless!

What are "our key requirements"?

It is likely that each evaluator will have their own opinion of 'what good looks like' and score accordingly. The scoring guide will not calibrate the scoring unless the evaluation team have discussed and agree what good looks like.

"I know it when I see it" is no substitute for being clear about what you are looking for! Worse than that, the evaluators may score the response against each other. "I liked #2 better than #3" is not good practice, but it happens. While you can't always influence the prospect's scoring processes, you can develop a self-assessment framework before you submit your proposal. Here is an example of a scoring guide focused on innovation:

Imagine that the proposal team could develop a response to the question above using this example as a guide to what "good looks like". Imagine that even if the prospect is dysfunctional and resorts to scoring responses relative to each other, and not against a standard scoring framework, your response had successfully calibrated their understanding of "what good looks like"?

Wouldn't that be worth having?

The ability to self-assess your proposal before you pressed 'send', and also the ability to shape the prospect's understanding of what good looks like!

Wow!

The dangers of self-plagiarism

March/2021/

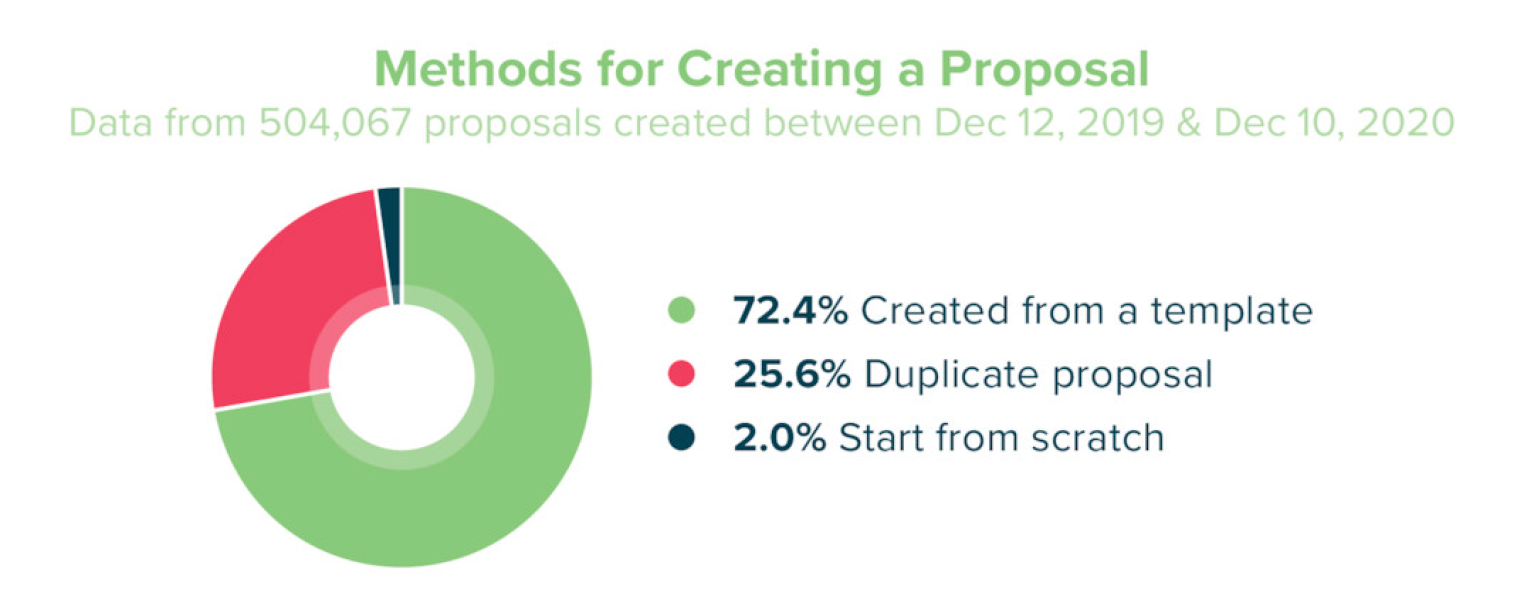

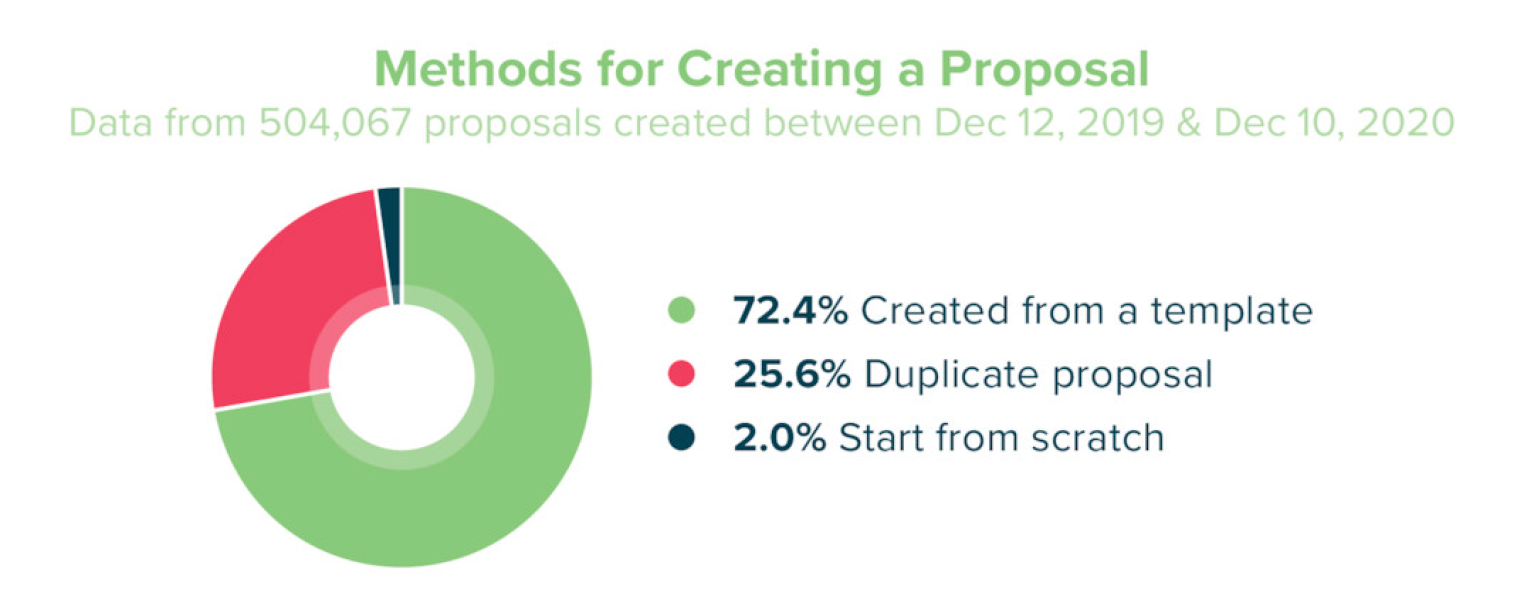

That more than a quarter of all proposals are based upon a previous proposal is no surprise to procurement practitioners. I have seen proposals where the search and replace of the recipient's company name was only partially successful. Part-way though the proposal stopped mentioning the name of the intended recipient and instead stated the name of the previous company that this proposal had been sent to!

#epicfail

The practice of 'adapting' the content for prospect B based upon the content sent to prospect A works well for unsolicited proposals, or when the prospects have similar needs.

But what if they are prospects in different sectors with different needs?

And what if prospect A had asked some specific questions, and the (lazy?) salesperson replicated the responses to prospect B?

Source: Proposify

This reminds us that there are three types of content in proposals:

But what if the content contains some 'type 3 content' that has been originated for another purpose?

Be careful. Self plagiarism may cause you to present to prospect B solutions that solve the problems of prospect A!

#epicfail

The practice of 'adapting' the content for prospect B based upon the content sent to prospect A works well for unsolicited proposals, or when the prospects have similar needs.

But what if they are prospects in different sectors with different needs?

And what if prospect A had asked some specific questions, and the (lazy?) salesperson replicated the responses to prospect B?

Source: Proposify

This reminds us that there are three types of content in proposals:

- Standard content that is unchanging, such as your ABN

- Configurable content that is largely unchanged, but may contextualised for different prospects, such as case studies

- 'Bespoke' content that is originated exclusively for a specific proposal, such as answering an RFP question

But what if the content contains some 'type 3 content' that has been originated for another purpose?

Be careful. Self plagiarism may cause you to present to prospect B solutions that solve the problems of prospect A!